Saturday, July 30, 2011

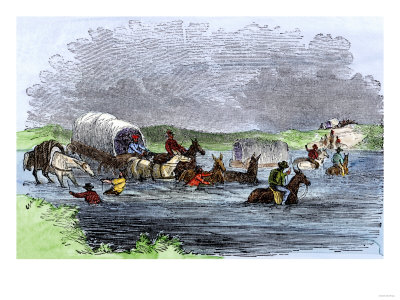

PIONEERS ON OREGON TRAIL

The first land route across what is now the United States was partially mapped by the Lewis and Clark Expedition between 1804 and 1806. Lewis and Clark initially believed they had found a practical overland route to the west coast; however, the two passes they found going through the Rocky Mountains, Lemhi Pass and Lolo Pass, turned out to be much too difficult for wagons to pass through without considerable road work. On the return trip in 1806 they traveled from the Columbia River to the Snake River and the Clearwater River over Lolo pass again. They then traveled overland up the Blackfoot River and crossed the Continental Divide at Lewis and Clark Pass and on to the head of the Missouri River. This was ultimately a shorter and faster route than the one they followed west. This route had the disadvantages of being much too rough for wagons and controlled by the Blackfoot Indians. Even though Lewis and Clark had only traveled a narrow portion of the upper Missouri River drainage and part of the Columbia River drainage, these were considered the two major rivers draining most of the Rocky Mountains, and the expedition confirmed that there was no "easy" route through the northern Rocky Mountains as Jefferson had hoped. Nonetheless, this famous expedition had mapped both the eastern and western river valleys (Platte and Snake Rivers) that bookend the route of the Oregon Trail (and other emigrant trails) across the continental divide — they just had not located the South Pass or some of the interconnecting valleys later used in the high country. They did show the way for the mountain men, who within a decade would find a better way across, even if it was not to be an easy way. In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson issued the following instructions to Meriwether Lewis: "The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri river, & such principal stream of it, as, by its course & communication with the waters of the Pacific Ocean, whether the Columbia, Oregon, Colorado and/or other river may offer the most direct & practicable water communication across this continent, for the purposes of commerce." Although Lewis and William Clark found a path to the Pacific Ocean, it was not until 1859 that a direct and practicable route, the Mullan Road, connected the Missouri River to the Columbia River. To complete the journey in one traveling season most travelers left in April to May—as soon as there was enough grass for forage for the animals and the trails dried out. To meet the constant need for water, grass, and fuel for campfires the trail followed various rivers and streams across the continent. The network of trails required little initial preparation to be made passable for wagons. People using the trail traveled in wagons, pack trains, on horseback, on foot, and sometimes by raft or boat to establish new farms, lives, and businesses in the Oregon Country. Once the first transcontinental railroad by the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific was completed in 1869, the use of this trail by long distance travelers fell off because the train took seven days and at $69 was much cheaper. Travelers going to Oregon could take the train to California and catch a coastal steamer to Oregon. By 1883 the Northern Pacific Railroad had reached Portland, Oregon, and thereafter there were less and less wagon trains each year along the western trail. The legacy persisted as highways such as Interstate 80 followed the same course westward and passed through towns originally established to service the Oregon Trail. Oregon Trail travelers could purchase repairs, new supplies, fresh teams and help from fort-trading posts such as Fort Kearny and Fort Laramie. Jim Bridger's Fort Bridger and Hudson's Bay Company owned: Fort Hall and Fort Boise in Idaho; Fort Nez Perces (Fort Walla Walla) in Oregon and Fort Vancouver in Washington. Other supplies, fresh teams and repairs could often be obtained from temporary trading posts and ferries set up by entrepreneurs along the trail during the traveling season. From the early to mid 1830s, but especially after the organization of the first large wagon trains in Independence, Missouri in 1841 and through the epoch years 1846–1869 the Oregon Trail and its many off shoots was used by about 400,000 settlers, ranchers, farmers, miners, and businessmen and their families. The eastern half of the trail was also used by travelers on the California Trail (from 1843), Bozeman Trail (from 1863), and Mormon Trail (from 1847) which used many of the same eastern trails before turning off to their separate destinations. The eastern part of the Oregon Trail spanned part of the future state of Kansas and nearly all of what are now the states of Nebraska and Wyoming. The western half of the trail spanned most of the future states of Idaho and Oregon. From various "jumping off points" in Missouri, Iowa or Nebraska, the routes converged along the lower Platte River Valley, near Fort Kearny, Nebraska Territory. Small steamboats carrying fur traders navigated the Missouri River up to the Yellowstone River in Montana as early as 1832. Larger steamboats traveling much above St. Joseph were blocked until dredging opened a bigger channel in 1852. After 1840 steam-powered riverboats and steamboats traversing up and down the Ohio, Mississippi and Missouri rivers sped settlement and development in the flat region from the Appalachian mountains to the American Rocky Mountains. The boats serviced the jumping off points for wagon trains that crossed the mountains headed to rich farmlands in Oregon and California. With disputes with Spain and Britain settled by 1848, the new lands proved highly attractive. Getting there by sea meant either a very long trip around South America or through Panama—both were expensive and dangerous and took longer than walking. The Oregon Trail is a 2,000-mile (3,200 km) historic east-west wagon route that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon and locations in between. It flourished from the 1840s until the coming of the railroad at the end of the 1860s. The trip on foot took four to six months. It was the oldest of the northern commercial and emigrant trails and was originally discovered and used by fur trappers and traders in the fur trade from about 1811 to 1840. In its earliest days much of the future Oregon Trail was not passable to wagons but was passable everywhere only to men walking or riding horses and leading mule trains. By 1836, when the first Oregon wagon trains were organized at Independence, Missouri, the trail had been improved so much that it was possible to take wagons to Fort Hall, Idaho. By 1843 a rough wagon trail had been cleared to The Dalles, Oregon, and by 1846 all the way around Mount Hood to the Willamette Valley in the state of Oregon. What became called the Oregon Trail was complete even as improved roads, "cutouts", ferries and bridges made the trip faster and safer almost every year.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment